1961: From Dream to Reality in Half a Year

It was on a cold January evening in 1961 when Ruth Jones attended a talk on small-town tourism and the seeds of an idea took root. Ruth and her husband, Dr. Casey Jones—Orillia residents and folk music enthusiasts—often made the drive south to the coffee houses and folk clubs of Toronto. The only modern folk festival in North America at that time was the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island. Within days Ruth was placing a call to Pete McGarvey, a local broadcaster and town alderman, to share her idea – Pete loved it. Together they agreed that Orillia needed a folk festival, and they would create one that very summer.

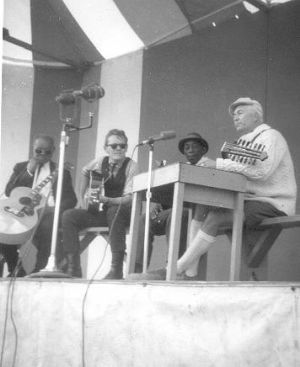

Source: Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections

From the first board meeting in February, there was only six months to plan the festival for the proposed festival date in August. With Ruth as president, Pete as vice-president, and Casey as secretary-treasurer—along with the help of a $250 grant from the Orillia town council and the Jones’ own savings—they got to work.

Ruth sought advice from the Newport Folk Festival and approached contacts among the Toronto Guild of Canadian Folk Artists, including future artistic director Estelle Klein. They helped Ruth begin to organize logistics, assemble a line-up, and promote the fledgling festival. The board members agreed on the name Mariposa in honour of the town in Stephen Leacock’s novel Sunshine Sketches of a Small Town, a thinly veiled story about Orillia. Emerging star Ian Tyson designed a poster and logo. For the festival site they rented the Orillia Oval, a green space that housed the community centre and arena. Ruth sent letters, wrote press releases, gave radio, TV, and magazine interviews, and arranged for a promotional collar on all milk deliveries to summer cottagers. Most importantly, musicians began to sign on for a Canadian-focused line-up of established and emerging artists that would eventually include The Travellers, Alan Mills, Jacques Labrecque, Jean Carignan, Mary Jane and Winston Young, and Ian Tyson and Sylvia Fricker.

An estimated 5,000 people swarmed to Orillia the weekend of August 18, 1961. The stage was set with an elaborate medieval tent – from which Ruth Jones would later write, “one expected knights to emerge for a jousting competition, rather than long-haired folkies with guitars and banjos.”. Orillia mayor George McLean welcomed the audience and Ruth Jones cut the ribbon to open the festival, then the music began. After the Friday evening concerts, hundreds joined a joyful street dance on Orillia’s main street. Saturday featured films about folk music, a free children’s concert, a symposium on Canadian folk, and more performances. Concerts cost $2 for one or $5 for three.

The Globe and Mail report on the inaugural festival focused on a disconnect between traditional artists and audiences looking for a more commercial sound. Applause was often more dutiful than loud, and the crowd more mystified than understanding. But slogan-heavy protest songs were a hit, as were the folk group The Travellers, bluegrass band The York County Boys, singer-songwriter Bonnie Dobson, and coffee house favourites Ian & Sylvia.

To the musicians, the festival was an unequivocal boon. Jean Carignan spoke to the local Packet and Times newspaper calling the Mariposa Folk Festival “the greatest thing in folk music I have ever seen in Canada”.

1962: “A ‘Crashing’ Success”

Source: Clara Thomas Archives & Special Collections

Ruth and Casey Jones’ financial support for the festival had extended to taking out a mortgage on their home. By the time the first festival wrapped, Mariposa was $4,000 in debt and the Jones’ financial reserves were depleted. If there was going to be a Mariposa 1962, something had to change. So when Toronto entrepreneur Jack Wall offered to buy the rights to Mariposa for $2, clear all debt, and manage the festival going forward, there was little choice. Wall took over—with Ruth Jones maintaining creative control—and planning began for 1962.

The line-up for the second festival was mostly a repeat of the first, with the addition of Canadian-born American folk singer-songwriter Oscar Brand along with Orillia native and Mariposa legend Gordon Lightfoot. In 1961 festival organizers turned down Lightfoot and his partner Terry Whelan for being “too commercial”, but when they were invited to perform in 1962, they were a hit!

Thousands flocked to Orillia, and hotels were fully booked. Townspeople offered rooms in their homes, while some festivalgoers slept in the park, on the beach, or on people’s lawns. On Friday night the main street was once again closed for a dance party. This was the year the Mariposa workshop established itself as a festival staple, with a popular workshop on folk music as entertainment and another hosted by singer-songwriter Ed McCurdy, giving aspiring singers the opportunity to perform and receive feedback. More than 6,000 attended Saturday evening’s concert, and many kept going all night long at impromptu hootenannies.

But the throng remained peaceful. The greatest source of conflict was whether the festival should stay all-Canadian or bring in American stars, focus on traditional folk music or embrace a more commercial sound.

In the words of the Toronto Star headline, the second Mariposa festival was “a ‘crashing’ success.”

1963: Disaster

Source: Mariposa Folk Foundation

Then came 1963.

For the third festival, with reports of fully-booked hotels and folkies coming from as far away as Detroit and Winnipeg, the Orillia town council decided to break out the bunting—literally. The royal bunting had been in storage since Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip’s visit in 1959, but in 1963 the town of Orillia brought it out in honour of what was becoming a vibrant and important festival, not just locally but nationally and internationally.

In fact, with two successful festivals behind it, it improved the publicity and plenty of word of mouth – Mariposa was touted everywhere as the place to be.

And the people came.

Friday evening of the festival weekend, despite rainy weather, the highway from Toronto was jammed with cars on their way to Mariposa. CBC Television sent crews, as did NBC and various radio stations. By the time numbers reached their highest, this town of 15,000 had drawn a crowd variously estimated at 20,000 and 30,000 people.

The town’s resources were overwhelmed. Hotels overflowed and restaurants ran out of food. The concerts and workshops carried on, but by Saturday night the celebration had tipped into debauchery. The streets and park were taken over by drunken revellers, motorcycle gangs arrived for the party atmosphere and students more interested in partying than music, including underage drinkers. They blocked traffic with their grocery cart races, threw broken wine bottles in the streets, broke into fistfights, vandalized local businesses and homes, ransacked parked cars, and bathed the statue of Samuel de Champlain in beer. There were countless reports of theft, and police were overwhelmed. They charged, jailed, and then—needing to make room for more—released people as soon as they sobered up.

“It would take five hundred officers to handle that mob,” police chief Edward McIntyre said, “and we had only 30 this weekend.”

Afterward now-mayor Isabel Post told The Globe and Mail she was convinced that the festival itself was not a problem, but the “accompanying brawl and its resultant publicity and side effects were disgusting.” She soon took a stronger stance, promising to bar all future festivals from Orillia. Even founding board member Pete McGarvey agreed that it was obvious Mariposa had to go. Within 10 days the town council had passed a resolution banning the Mariposa Folk Festival.

1964: Survival

With the festival evicted from Orillia and beset once again by financial woes, the future wasn’t bright. The festival had also lost two crucial founding members – Ruth Jones had moved away, and Pete McGarvey, pulled between conflicting roles as town Alderman and Mariposa board member, had resigned.

Toronto radio announcer and folk aficionado Randy Ferris, stepped up to the role of president and persuaded Estelle Klein to take on the artistic directorship. In June he announced a new plan – the festival would take place on a farm in Medonte Township, 12 miles west of Orillia. Lawyers assured Ferris that Medonte Township couldn’t prevent the festival from going forward on private property. Ferris planned enough security presence to handle a crowd of 50,000, with payment required to get within a quarter mile of the concert area to dampen the interest of anyone not there for the music.

The Globe and Mail article speculated that the festival would have trouble securing performers, who would now be “as wary of the name Mariposa as are Orillians.” But Klein curated a program that included Gordon Lightfoot, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Mississippi John Hurt, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and tickets were selling.

But then the Medonte Township council, uneasy about a potential repeat of 1963, passed a bylaw. To hold the festival there, Mariposa would have to pay a $200,000 bond of liability – a fortune, especially in 1964. Mariposa had four days to come up with the money, but they couldn’t. On July 31, one week before the opening on August 7, Medonte Township filed an application for an injunction restraining the Mariposa Folk Festival from going forward.

Mariposa Folk Festival responded with what seemed the only recourse. They filed a motion to quash the bylaw on grounds that it was prohibitive, and then applied for a hearing before the Ontario Supreme Court for a temporary court order preventing Medonte officials from enforcing the bylaw. The date of the hearing was on August 6, the day before the festival was scheduled to open.

The court ruled against Mariposa.

Photo by Jim Yates

Over several frantic hours with stages, wiring, and lighting all set up at the farm and the festival’s Toronto office besieged by ticket holders demanding their money back, festival organizers scrambled to work out a compromise with Medonte Township while simultaneously hunting down an alternate venue.

Ferris announced the location change 24 hours before the scheduled opening of the first concert. The Toronto Maple Leafs baseball team was on the road that weekend; the Maple Leaf Stadium (at the base of Bathurst Street south of Lakeshore Boulevard) was available to rent. Mariposa 1964 would be held at a baseball park.

The organizers attempted a media blitz, but it was not much time to get word out about the new venue. On Friday night, only 500 people showed up. Even performer Buffy Sainte-Marie had to be retrieved from the airport, where she’d booked a flight out of Toronto on hearing that the festival was cancelled.

The fourth Mariposa Folk Festival limped forward – it rained, the temperature hovered around 12 degrees and the huge baseball stadium was nearly empty.

But from under their umbrellas, audiences got to witness Gordon Lightfoot’s debut of his just-written ‘Early Morning Rain’. Estelle Klein’s programming gave them Canadian, American, and Indigenous acts with performers such as Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, and Isaac Beaulieu. Buffy Sainte-Marie delivered a performance so compelling she was called back for four encores.

Four years old, in the face of incredible challenges and almost insurmountable odds, the Mariposa Folk Festival had survived.